From Provocative to Productive: Teaching Controversial Topics

Get first steps for creating a respectful yet vibrant environment for students to explore diverse ideas on controversial topics, from politics to profanity, religion to racism.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Current Events

- Politics

- Religious Liberty

- 6-12

The Newseum is committed to advocating for the First Amendment. The 45 words that protect freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly and petition are carved 74 feet high in stone on the front of the building. But since its ratification in 1791, this amendment has engendered vigorous debate – sometimes civil, sometimes not – about exactly what these freedoms should mean and how they should apply. With these debates touching on topics from politics and public protests to racial tensions and religion, teaching about the First Amendment inevitably invites controversy. But rather than back away from these potential flashpoints, we believe that the passion and interest these topics elicit can make them a powerful teaching tool.

The four guidelines and debate leader checklist below, based on NewseumED’s experiences and widely held best practices, provide a foundation for those seeking to steer productive conversations about controversial subjects. Yet the success of a conversation about a controversial topic depends on many factors, from the facilitator’s preparation to the mood of the students on the given day. Some of these you can control and some you cannot. These guidelines are designed to help you prepare and plan for as many of the controllable factors as possible and create a flexible environment and experience that can meet your students at their level. Think about these conversations as embarking on a sort of “choose your own adventure” lesson plan. Be prepared to twist and turn in response to your students’ questions and answers, and keep in mind that the measure of success will not be a single final product, but the overall exchange of ideas.

We want to hear your ideas, too! Share your tips for teaching about controversial topics with us at [email protected].

To be confident in your content, you must be two things: prepared and committed.

Being prepared means reading up on any necessary background material in order to feel comfortable with the topic at hand and share it in a way that meets your participants’ needs. You don’t have to be an overnight expert, but you do need to anticipate the types of basic questions your students might have and be prepared to answer them. You should also be prepared to be honest about what you don’t know. If a student asks a question that falls outside of what you’ve reviewed, commend them on their insight and make a plan to find the answer – immediately, if you’re wired and teaching an informal lesson, or later if that makes more sense.

Being prepared also means having solid resources ready to share with your students that can help shape and scaffold their conversation. The Freedom in the Balance EDCollection provides reliable, fact-checked resources including case studies, scaffolding questions and worksheets; we design these resources to help students confront new ideas and develop well-reasoned opinions.

The other element of confidence in your content is being committed. Being committed means believing that the conversation you are undertaking, while it may take effort to prepare and may lead to some uncomfortable moments, is a worthwhile endeavor. Establish a clear learning objective and commit to helping your students reach it. Think about why you’re having this conversation and how to convey that purpose to your students.

Every teacher has heard the adage about student performance rising to meet expectations. When dealing with controversial topics, it is particularly important to enter the conversation with elevated but realistic expectations that respect your students’ own ideas and agency.

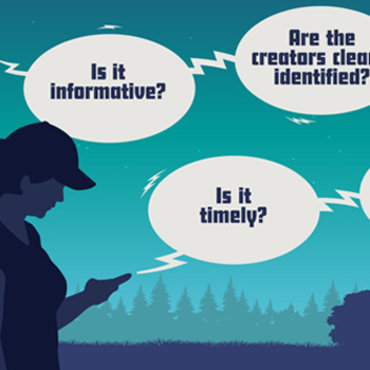

The first part of respecting your participants is trying to understand their mindset and frame of reference for the topic you’re discussing. The adolescent mind can be a mysterious place, but make a sincere effort to predict how your students will approach the topic at hand. What do they already know about it? What will they be curious about? What will make them laugh? Groan? Clam up? Thinking in advance about these reactions won’t necessarily make it possible to avoid them, but you can plan to emphasize the elements of the conversation that will bring out the best in your students and not get caught off guard by their reactions. By thinking through your participants’ perspectives, you can also be sure you’ve picked an appropriate topic. Almost all groups can engage in productive conversations about a difficult topic, but not every difficult topic is a good fit for every group.

The second part of respecting your participants is giving them clear information about what they will be talking about, why and how. Students can’t meet your expectations if they don’t know what they are. So refer back to the objective you set with Guideline 1 and find a way to spell out the purpose of your conversation and how it will take place. Who will talk when? What should they do if they disagree with an idea? What if time runs out before they’ve had a chance to be heard? Laying some ground rules will make participation feel less risky and quell some potential frustrations.

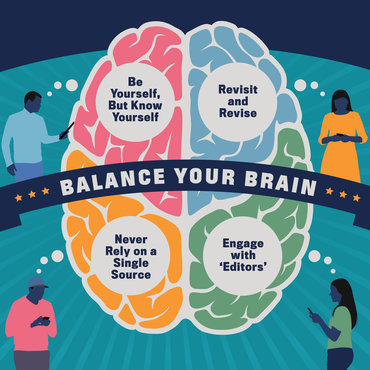

The final part of respecting your participants is valuing their ideas. Make it clear to your students that you’re inviting them to join this conversation because you genuinely want to know what they think – and make sure your actions back up your interest. Haven’t you ever wondered what goes on in those brains? Treat this as your chance to get a peek inside. Listen attentively. Don’t cut them off unless it’s necessary, and don’t immediately discount even the strangest statement, but rather ask for more explanation. There’s more on fostering a positive exchange of ideas in Guideline 4: Encourage debate.

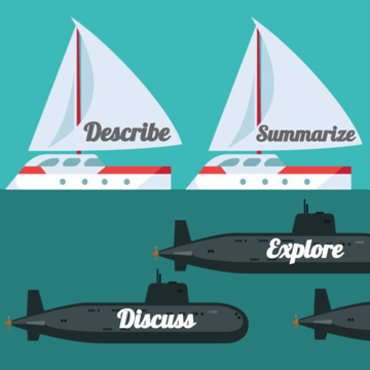

Every productive discourse about a controversial topic should be modeled on a genuine conversation with a give-and-take of ideas, not a lecture. From the beginning, make it clear to students that their participation is vital and that their ideas will drive the experience. Then use tiered questions to help your students ramp up into the topic at a pace that won’t overwhelm them. Like a streamlined version of Bloom’s Taxonomy, you should plan a series of questions that will move your students from basic comprehension of facts through analysis and evaluation of ideas.

As the leader of the conversation, avoid spending too much time on up-front explanation that might put your students into an information-receiving mode rather than an information-sharing mode. Instead, let your students provide as much of the needed background as possible, and let their own questions drive the information you share. For example, if you’re opening the conversation by looking at one of the 9/11-related images that frames the case studies, ask students about their own knowledge about the events of 9/11 and its aftermath. To fill in the holes, ask them what questions they have about what happened and answer as best you can, or point students to other resources that will help them fill in these gaps in knowledge.

As you get into the meat of the conversation, help shape it by feeding students questions that build toward more complex debate and analysis. For example, if you’re planning a discussion around a contemporary case study from Freedom in the Balance, begin by asking students to recap the information that’s in the case study. This both reinforces important facts and gives students a straightforward way to begin participating in the conversation.

Then move on to what position they would take. NewseumED believes that providing multiple-choice responses for these types of case studies broadens the conversation rather than narrowing it, by giving students a safe way to answer a very daunting question. You avoid the dreaded silence that follows a question students aren’t prepared to answer. Always make it clear to students that they can invent their own response or alter the given responses to better express their own ideas. Finally, move into discussion of why they made this choice and allow them to begin engaging with each other over differences of opinion. There’s much more on how to foster a productive debate in Guideline 4.

If you ever do encounter silence, try to rephrase your question or take a step back to re-engage your students. If, for example, they’re unable to explain the reasoning behind their choice, ask why they didn’t choose another option, or what outcome they think this option will lead to, or zero in on a specific element of their chosen response.

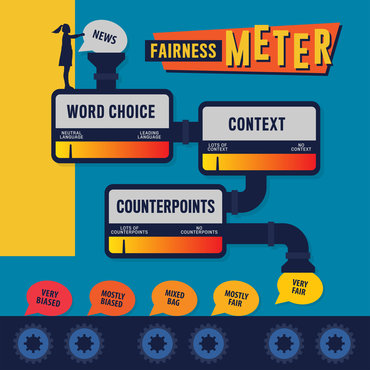

When discussing a hot-button topic, the goal should be a healthy debate, not a final answer. In some instances, a consensus may begin to emerge, but even then, your role as the facilitator should be to find ways to continue pressing students to refine and defend their ideas. To encourage a vigorous debate: create an even playing field, exact the benefits of small and large group discussions, and stir the pot by providing counterpoints to every side of the debate.

First, maximizing participation in this type of debate begins with evening the playing field. No students should feel that are at a disadvantage due to a lack of prior knowledge or experience. The NewseumED case studies are designed to help achieve this goal by spelling out a specific scenario and providing options for action. There’s no way and no need to bar outside knowledge from influencing the debate, but the structure of these case studies is meant to allow even those who’ve never encountered this topic before to begin forming and sharing ideas.

To further nurture a healthy debate, give your students time for small group as well as class discussion. By discussing the case studies independently in small groups, students have the opportunity to try out their raw ideas in a less intimidating setting than raising their hand and their voice in front of the whole class. This practice also ties back in to Guideline 2 by showing that you respect their ability to discuss and engage with these ideas on their own. The multiple choice format helps keep them focused on an end goal.

Following small group discussion, coming together as a class provides an opportunity to present a broader range of ideas and begin testing and defending the ideas that came out of the small group discussions. Choosing a spokesperson to share the conclusions reached by each group is a good way to open the larger-scale debate and build the momentum for others to share ideas, including new thoughts that come out of the larger-scale exchange.

Finally, the key to keeping the debate vibrant and active is for the facilitator not to stay neutral, but rather take all possible sides of the debate. By taking on the role of official pot-stirrer, the facilitator can inject energy into the debate to ensure that no voice or voices become unfairly dominant. At the Newseum, the NewseumED educators often think of our role as playing devil’s advocate. We are purposefully contrary and challenge as many ideas as possible. This serves two useful purposes. First, it allows us to shape the debate to make sure as many perspectives as possible are heard and protects us from being perceived as taking any single side. Second, it feeds on middle- and high-school students’ innate desire to argue with authority. In this case, their contrary nature is an asset and helps drive the debate.

Before the debate

- Read up on the topic of the debate.

- Establish and commit to an objective for engaging in this debate.

- Think about your participants’ possible perspectives on and responses to this issue.

- Find or prepare background/debate materials as needed to create an even playing field for all participants.

- Write or think through possible questions you can ask to introduce the topic and guide the debate, ranging from straightforward to complex.

During the debate

- Share the objective for engaging in this debate.

- Set ground rules for participation.

- Ask questions to encourage participation and guide the debate, ranging from straightforward to complex.

- Listen to participants’ ideas and ask for clarification as needed.

- Allow time for small and large group discussions.

- Do not take a side; instead play devil’s advocate and present opposing viewpoints to balance the debate.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.3

Evaluate a speaker's point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.4

Present information such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

-

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.4

Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.